[Present dispensation in China is engaged in creating a harmonious society in China and the burgeoning problem of water shortage is likely to upset its ambitious aspirations as counties affected may give rise to unmanageable problems. The rivers emanating from Tibet, while passing through Tibet stream downward the neighboring countries. Brahmaputra and Sutlej which originate from Tibet flow down into India. However, China’s contemplated move to build dams along Sino-Indian border can adversely impact India, Ed.]

The present regime under the leadership of President Hu Jintao in Beijing is pursuing the policy of hexie shehui or the harmonious society, which envisages social and political stability based on sustainable development and people’s welfare. However, the Chinese society is afflicted with severe water scarcity and pollution, which seems a clear fault line in its path to the society. The problem of water scarcity has threatened the Chinese people’s sustenance; caused grain loss; brought about acquire depletion and its following land subsidence and seawater penetration; induced water-seeking migration; and, significantly, triggered conflicts and protests for water.

Undoubtedly, China’s leadership is highly aware of the gravity of the problem and has been attempting to contrive water-conservancy programmes. However, as is discernible from the Yellow River Allocation Programme, the water consumption quota system/water price increase, and forestation programmes demonstrate, the programmes have not been implemented effectively due to their institutional flaws as well as the local government’s parochialism and corruption.

On the contrary, China’s water pool has been seriously drying or decaying, causing not only grain loss but also social disruptions including conflicts and protests, which has thwarted the goal of China as a ‘harmonious society’. Additionally, China’s major programmes for water conservancy have not been successful either.

Magnitude of Water Scarcity

Apparently, China’s water pool has almost been hassle free. According to Beijing’s own estimation of its national water resources, which was conducted between 1979 and 1985 to cover the 24 years from 1956 to 1979, the total annual water resources was 2812.5 billion cubic meters, which ranks sixth in the world. Presently, China has 7 percent of the world’s fresh water.

Currently, the actual per capita water consumption in China for all purposes – agriculture, industry, services and households – is merely about 450 cubic meters/year. It is a fifth of the per capita water resources of China (at most 2, 222 cubic meters), which is already two-sevenths of the world average of the per capita water resources.

Water deficit is especially severe in northern China: with only one-fifth of the water resources of China, the region has to supply water to two-fifths of the population and two-thirds of the crop land. The Luan/Hai River Basin has the highest water deficit rate (16.4 %). Another representative illustration of northern China’s water scarcity is the faltering Yellow River. With less precipitation and the stiff increase of consumption, the Yellow River’s flow reaching the seas has diminished from 385 billion cubic meters in 1950s and 1960s to 134 billion cubic meters in 1990s.

The Yellow River has even undergone cut-offs since 1972. Cut-offs were observed downstream for 20 years out of 26 years between 1972 and 1997; the total cut-off times during this period reached 70; and, the cut-off days came to 908 (45 cut-off days/year on average). It bodes ill for the future that the temporal and spatial length of Yellow River cut-off is increasing.

It is noteworthy that the cut-off lengths were measured from the cut-off points to the Lijin hydrometric station, which is still 136 kilometers up from the river’s mouth. Thus, the actual cut-off lengths and periods in which no drop of the Yellow River could meet the seas are much longer. Under the present circumstances, people in China are worrying that the Yellow River will probably devolve into an inland river someday.

The water shortage and pollution in China is directly threatening its people’s well-being. The water scarcity caused by a record-breaking drought in northern China in the summer of 2000 left more than 6 million people without an adequate amount of water. Due to contamination, almost 700 million Chinese drink unsafe water; it causes their gastrointestinal cancer or deaths of their children. In addition, the water scarcity/pollution has induced economic losses and social disruptions in China.

With the lack of irrigation water, China annually undergoes at least 15-20 million tons of grain loss. According to a report released by Beijing in spring 2007, China’s production of wheat, rice, and corn, will be reduced by 37 percent in the latter half of the century with decline of precipitation.

Viewed in a broad spectrum, along with the insufficiency of surface water, groundwater has been severely tapped. As early as in 1996, 3.6 million wells were already located in the North China Plain only, which yields more than half of China’s wheat and almost a third of its corn. Presently, 34 percent of northern China’s total water supply relies on groundwater whereas 4.2 percent of southern China’s water supply comes from underground sources.

Heavy dependence upon groundwater in China has resulted in aquifer depletion, which, in turn, has triggered land subsidence across China. Cangzhou, a northern base of chemical industries, has witnessed buckled roads, toppled buildings, and uprooted lamp posts, caused by groundwater overexploitation. Nine rifts run through the city of Xian, the historic capital of Shaanxi Province, placing 2,600 houses in danger. Reservoirs in Fuyang City, Anhui Province, have been cracked, distorted, or lowered.

Moreover, the overexploitation has also led to seawater intrusion. The ground surface of Tanggu area in Tianjin has fallen below the sea level and now is protected only by a dike. In Shandong Province, the areas under seawater seepage in Lanzhou City and Longkou City are 234-square-kilometers and 91-square-kilometers, respectively.

In the wake of deteriorating conditions due to water paucity, people in drought-stricken areas leave their homes. Significantly, wherever “water migrants” settle down, they add new burdens to the local water pool; it sometimes triggers residents’ hostilities to block migrants’ access to water resources. During a dry spell in 2002, the villagers in Shenzhen actually prohibited migrants from drinking from their wells.

Recently, there have occurred cases of conflicts and even violence over water resources. In 2000, when 35 million acres of agricultural fields were parched due to the year’s drought, officials in Anqiu city, Shandong province, decided to block seepage from the Mushan Reservoir, one of the province’s biggest reservoirs, to direct the water to cities and industries. The local government decision provoked the vehemence of peasants since the seepage had been indispensable to their irrigation for a long time.

So, 5000 of them got together to crack down on the project; they broke into the reservoir management office and fought with 300 policemen lined up to disperse them. During the clash, one policeman was beaten to death and 100 peasants and forty policemen were wounded. It was reported by the Straits Times on 21 August 2000 that there had been ‘countless skirmishes’ in China between villages and townships over ownership of water resources. Some of the clashes claimed lives, such as the case of Hunan province where hundreds of villagers fought over control of disputed water catchment areas.

Shanxi Province’s Water Conservancy Chronology records a few water ‘disputes’ between cities or counties along provincial borders of Shanxi and Henan over the construction of hydro-electric power stations, which affected the amount of water resources available for each part involved. The Chronology argues that all the disputes have been basically resolved. However, according to a recent report of the Xinhua News Agency, officials of Hebei delivered complaints to the National People’s Congress in March 2008 that Shanxi had constructed more than 100 reservoirs to divert water from the border-crossing Zhanghe River and worsen water shortages of Hebei, which is supposed to supply Beijing with its 300 million cubic meters of water for the city’s Olympic Games despite the lack of drinking water for its 250,000 residents with a severe drought.

Overall, between 1990 and 2002, according to a 2003 report of the Ministry of Water Resources of China, there were more than 120,000 water quantity conflicts reported to the ministry. Besides conflicts and violence, water-related protests have caught attention of the Chinese government. Human rights groups have reported that incidents of peasants’ protests against taxes occurred in 2001 since the year’s drought ruined their crops. Protests have been also triggered by water pollution. In 2005, there were more than 50,000 environmental protests in China, and more than 50 percent of them were induced by water pollution.

It is true that Chinese political leaders have been aware of the severity of the water crisis and have pronounced their concern about it. However, the programmes they designed to alleviate the problem have not been effective not only with their own institutional flaws but also with local parochialism and corruption encountered in their implementation process.

Under the Yellow River Allocation Programme, local provinces along the river have frequently consumed more water than their quotas, causing tensions between upstream and downstream provinces, thanks to the lack of authority of the Yellow River Conservancy Commission which is in charge of the programme but placed below the provinces administratively. Individual water consumers do not care much about the penalties for their overconsumption under the water consumption quota system since water prices as the penalty base are quite low.

The prevalent scenario calls for re-examination of the major water-saving programs; as an important step to improve the programs, they as the central government should move from decentralization or ‘fragmented authoritarianism’ to stronger intervention in and coordination of provinces in order to put the programmes into force at local levels more strictly.

Implications for India

China’s hydro-engineering projects and plans in Tibet have serious implications for India.

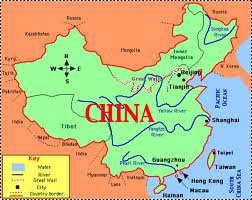

Through its control over the Tibet, China controls the flow of several major river systems that are a lifeline to southern and south-eastern Asia. However, China is toying with massive inter-basin and inter-river water transfer projects. Beijing has embarked on an ambitious project, Great South-North Water Transfer Project, which is an engineering attempt to take water through man-made canals to its semi-arid north.

China and India already are water-stressed economies. The spread of irrigated farming and water-intensive industries and a rising middle class are drawing attention to their serious struggle for more water. Although India’s usable arable land is larger than China’s — 160.5 million hectares compared to 137.1 million hectares — the source of all the major Indian rivers except one is the Tibetan plateau. Though the River Ganges originates on the Indian side of the Himalayas, yet its two main tributaries flow in from Tibet, the world’s largest plateau. Tibet’s status is unique wherefrom almost all the major rivers of Asia originate.

According to media reports, China is contemplating to build the world’s biggest hydropower plant on Brahmputra River’s Great Bend. China’s upstream projects have already been instrumental in causing flash floods in the Indian side of Arunachal Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh. India has repeatedly conveyed its serious concerns in this regard to the Chinese authorities who seemingly have made half-hearted attempts to assuage India’s apprehensions. Besides, China’s claim over Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh is another cause of irritant, apart from the diversion of waters of Brahmputra River.

These issues entail the potential of causing tension in the Sino-Indian relations. According to one expert, the way to forestall or manage water disputes in Asia is to build cooperative river basin arrangements involving all riparian neighbours. Such institutional arrangements ought to centre on transparency, information sharing, pollution control and a pledge not to redirect the natural flow of trans-boundary Rivers or undertake projects that would diminish cross-border flows.